How to get

7. Andre kalea

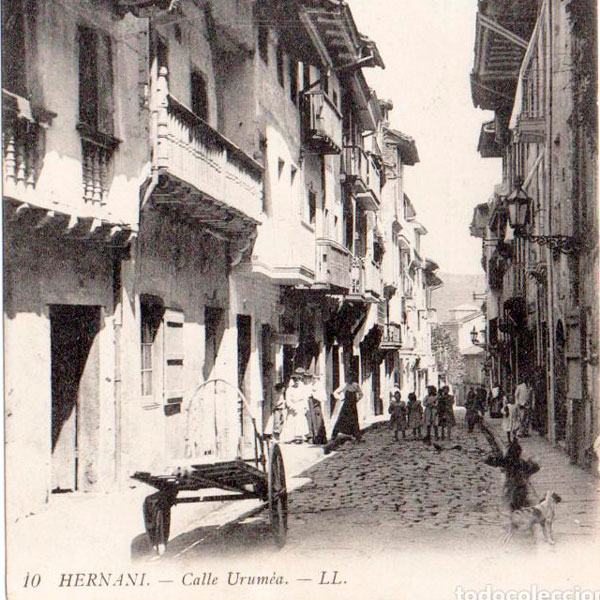

Andre kalea

Cider

Andre kalea is the “other” street that made up that medieval Hernani. Looking at the buildings, it is easy to conclude that Kale Nagusia was the street of the wealthy:successful merchants and aristocracy, mainly. In Andre kalea lived the humbler working classes, in simpler houses. They were originally two-storey buildings; the ground floor was used to store perishable foodstuffs and cider, and the living quarters were upstairs.

Most of them are separated by a firewall; fires have been a constant in Hernani’s history, and curbing their destructive power, a real obsession. The 1542 Ordinances already stated that the houses had to be built in “lime and stone”, avoiding wooden constructions. The Council also assumed the costs of extraordinary measures, such as the demolition of houses adjacent to a fire source, or, given that access to water was difficult, the use of cider as a means of smothering the fire.

Perhaps the most interesting chapter, however, is the link between cider and Basque seafarers. The Basques learned navigation and shipbuilding techniques from the Vikings. From the Middle Ages they traded whales, becoming the world leaders in this industry. It was in search of fishing grounds that they reached the North Sea, Iceland, Greenland and finally Newfoundland, possibly in pre-Columbian times.

These were complex expeditions lasting several months, where drinking water was a problem, as it became corrupted over time. The solution was a mixture of water and cider. It is estimated that each seafarer drank about three litres per day, totalling 50,000 litres for 8/9 month expeditions. Probably without knowing it, cider provided them with the nutrients and vitamin C they needed to avoid getting sick and scurvy.

Nowadays, the start of the cider season – the “txotx” – has become a social event, which transcends our territory, and the sagardotegis and the consumption of cider has become normal throughout the year.

Links of interest:

EVOLUCIÓN HISTÓRICO-CONSTRUCTIVA DE LOS EDIFICIOS RESIDENCIALES DEL CASCO HISTÓRICO DE HERNANI:

Cider:

http://www.sagardoarenlurraldea.eus/eu/